Ikat is a distinctive, hand-dyed textile characterized by its blurred, feathered patterns achieved through a complex dye-resist technique applied to the yarns before weaving. The term “ikat” derives from the Malay-Indonesian word mengikat, meaning “to tie” or “to bind,” and refers to the process of tying threads to resist dye penetration. This ancient method produces fabrics with mesmerizing, slightly hazy designs that embody the cultural heritage and artisanal craftsmanship of Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

The ikat process begins before the loom is even set up. Yarns, either warp (vertical), weft (horizontal), or both, are carefully bound with waterproof material, such as waxed thread or plastic strips, in specific patterns. These bound sections resist dye during immersion, creating undyed areas that will form motifs once the fabric is woven. Multiple dye baths can be used for intricate multicolor designs, requiring precise alignment of the dyed threads during weaving. The hallmark of true ikat is its characteristic “blurriness,” where colors softly bleed into one another, reflecting the handmade artistry and the slight misalignments that occur naturally.

There are three main types of ikat: warp ikat, where the warp yarns are dyed before weaving; weft ikat, where the pattern is formed on the weft yarns; and double ikat, the rarest and most complex form, where both warp and weft are resist-dyed and perfectly aligned. Double ikat is produced in only a few regions worldwide, most famously in Patola silks of Gujarat, India, and in Tenganan village, Bali, Indonesia.

Ikat’s origins are difficult to pinpoint, as similar resist-dye traditions emerged independently in multiple cultures. The technique has deep historical roots in Indonesia, India, Japan, Central Asia, and Latin America, where it evolved uniquely in each context. In Indonesia, ikat holds spiritual and ceremonial significance, with motifs symbolizing fertility, protection, and ancestry. In India, regions such as Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Gujarat are renowned for their vibrant ikats, which are made from cotton and silk. Uzbekistan’s silk ikats, known as Adras or Khan Atlas, feature bold patterns and bright colors that once adorned royalty. Meanwhile, Japanese Kasuri and Guatemalan ikats show how the tradition transcended continents through trade and cultural exchange.

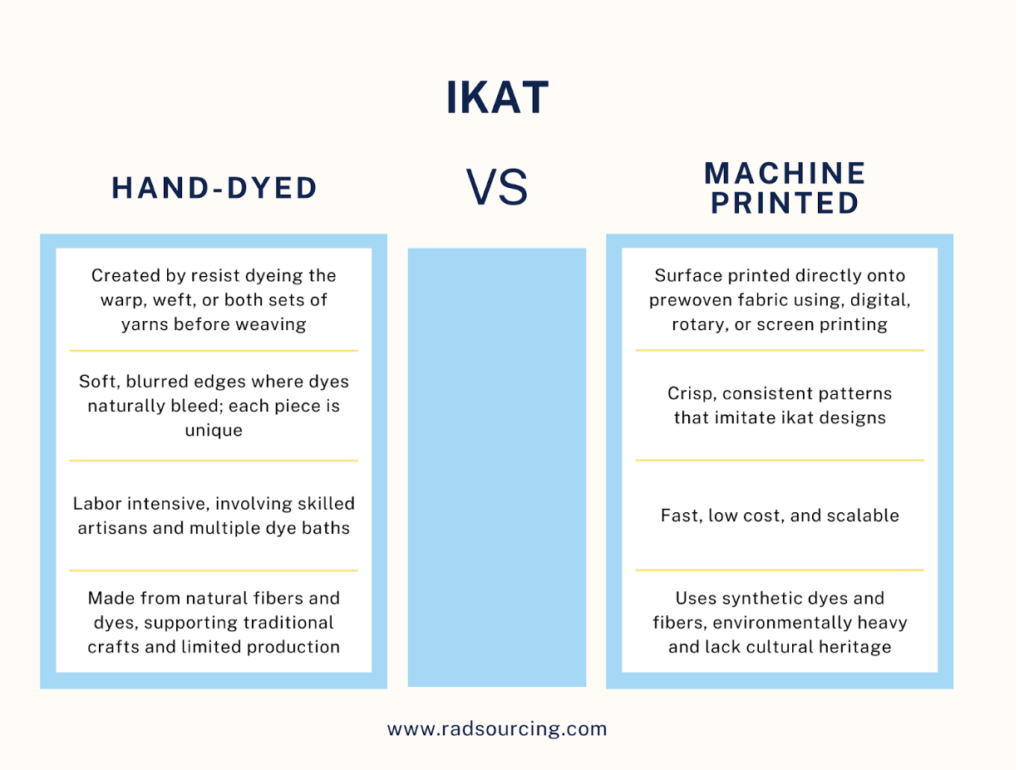

The properties of ikat vary widely depending on the fiber and dye used. Traditional ikats are crafted from natural fibers, including silk, cotton, and wool, utilizing dyes derived from plants, minerals, and insects. The resulting fabrics are soft, breathable, and rich in color variation. Ikat’s blurred edges cannot be perfectly replicated through printing, making each handmade piece unique. However, modern mass-market “ikat prints” mimic the pattern using digital or screen printing rather than resist-dyeing, reducing costs but losing the texture and artistry of authentic ikat.

In fashion, ikat is used in dresses, jackets, scarves, skirts, and accessories, often as a statement textile that blends tradition and modernity. In interiors, ikat is popular for upholstery, drapery, and cushions, where its organic, rhythmic patterns add cultural depth and visual warmth. Designers frequently incorporate ikat motifs into contemporary collections, celebrating their artisan origins while appealing to global aesthetics.

From a sustainability perspective, ikat stands out for its traditional, low-impact production methods. Handmade ikat typically utilizes natural fibers and dyes, employs small-scale dye baths, and relies on minimal machinery, thereby supporting local economies and preserving traditional cultural crafts. However, the process is time-intensive, making authentic ikat more expensive than printed imitations. Synthetic dyes and mass-produced machine looms can compromise sustainability, though many artisanal cooperatives now focus on eco-dyed, fair-trade ikat textiles.

Global centers of ikat production include India (Pochampally, Odisha, Patan), Indonesia (Bali, Sumba, Flores), Uzbekistan (Margilan), Guatemala, and Japan (Kurume, Okinawa). Each region maintains distinctive patterns, motifs, and symbolic meanings, ensuring ikat’s cultural diversity and ongoing relevance.

Ikat embodies the fusion of art, culture, and craft. Its blurred patterns tell a story of human skill, patience, and heritage, woven into every thread. Despite centuries of change, ikat continues to captivate designers and consumers alike, symbolizing both timeless tradition and global artistic dialogue.